Sitting down with three young, enthusiastic PhD researchers, the conversation just flowed.

Each is working in a completely different domain to the other, each is in a different faculty. The sole connecting thread is that their labs are collaborating members of the EPFL EcoCloud Center. That, and the fact they all use python to develop deep neural networks. This seems to be a growing trend!

In conversation, it became clear that they actually have a lot in common, based on their experience as EPFL researchers. Independently of each other, they have to come to many similar conclusions, from best research practices to the ethical use of AI.

What is the workload like, as a PhD researcher at EPFL?

"Better than I had thought," says Belén. "Everyone said it would be the worst time of my life but I feel that, compared to MSc or BSc, it's a lot nicer for life-work balance. Before, I could never do fun stuff at the weekends without feeling guilty."

Simla had received comparable warnings: "Before I started I heard a lot of horror stories, about how this is the hardest thing I will do in my life. It comes down to time management, knowing how to plan your workload. If you have the right mindset, taking a break after deadlines, it can be really enjoyable. Going to the mountains, going to cities in other countries - it balances the work."

"In the Masters there is a constant pressure," says Lara, "but with the PhD you have time between publication deadlines, and the other deadlines that you set for yourself. In our lab, we do not pressure each other to put in extra hours. Members go hiking, kayaking; there is a good balance.

"In several US PhD programs you have to take a heavier course load, you don't have defined vacations, and the salary is low compared to the cost of living in the big cities. At EPFL, PhD students are treated as employees, not as students. We have our weekends free, a fair salary, and we are even obliged to take 25 days of vacation."

"I find that too," agrees Belén. "But nowadays I feel the least I have been since starting high school - no stress about grades, less intense workloads and pressure. As an Undergraduate I was going out more, but almost feeling more guilty about it. Now I find myself doing things I am more interested in during my spare time, and I'm more enthusiastic about going in to work."

How does PhD research differ from your previous studies?

Lara: "A professor told me before I left the US: 'This where your life becomes non-linear. The results you get will not necessarily reflect the amount of effort you put in!' Sometimes I have a hard time separating my self worth from the success of my results."

This was met with agreement all round. "A small fraction of what you do is what brings most of the results," according to Belén.

"I tend to be quite hard on myself when my work does not go as planned" says Lara. "To deal with this, it is a good idea to have multiple things going on at once - several research projects , teaching, extra-curricular activities - so even if one thing isn't working I can find joy in the others."

How much access to professors do you get?

"In my experience it works out really well," replies Belén. "Supervisors can be good, but not good for you. In my case it is a great fit. I like to work independently, and my professor is happy with that. Some students might prefer micromanaging, but in my case he is aware that I put pressure on myself."

All three have weekly meetings with a professor or a leading scientist.

"Whenever I talk to my professor I feel like I have a lot to learn," laughs Simla.

"We are looking for my professor's hidden twin," jokes Lara, "he is always everywhere all at once!"

I pointed out, at this moment, that they all had male professors.

Are you ever made to feel you are in a male-dominated environment?

"Yes, but mostly during my Bachelor," says Simla. "People would ask, 'Wouldn't it be more suitable for a woman to be in Medicine rather than engineering?' Gender bias still exists."

Lara agrees: "During my Bachelor in group projects, when we were dividing up jobs, someone on the team would command: ‘OK, Bob is going to build the robot, Sam is going to write the code, Lara you can write the report.’

"So you end up doing extra work to prove that you can do the technical engineering jobs and not just the secretarial ones. Hopefully this is going in the right direction, the younger generation are seeing that women can be excellent engineers, without a doubt!"

Even AI can be gender-biased, according to Simla. "Using Google translation, if you translate ‘This one is a doctor, this one is a nurse' from Turkish to English, it will say 'He is a doctor, she is a nurse.' This is due to the training data used for AI, which is generated by humans.

"But that is changing. With ChatGPT, they use the Transformer architecture, and a mechanism called 'attention', where the choice of word can be inferred from the context. Researchers also add a lot of control into it to eliminate the learned gender bias."

"There is a data gender gap that needs to be addressed," agrees Lara. "Airbags in cars are less likely to save women, because most testing was done on males."

"It's really important that AI is guided by theory," adds Belén. If you use a black box and just trust the statistics, you can end up with results that don't make sense. There need to be constraints. Not only should the data be representative, but machine learning must make sense when you are using it.

"To what extent is it a problem of how you frame it, where do ethical and philosophical factors come in? Even if an algorithm is really powerful, if it isn't framed correctly, it's not going to take you anywhere."

"Which is why in our course on Machine Learning there is a module on ethics!", states Simla.

So where is AI leading us?

"They said that automatic cashdesks were going to put people out of a job," says Lara, "but in the end these automated systems are only for ten items or less, and there is an important job of overseeing."

"As Lara said, supermarket cashiers still have jobs even though there is a self-checkout option," adds Simla. "Technology just helped them reduce the workload and maybe even change the work definition. Because now, they just have to check the people doing self-checkout instead of doing it for them."

"Maybe society is going to be more obsessed with credentials," suggests Belén, "you can't know if it is machine learning that did some kinds of work, so reputation might be the way people judge work."

What advice do you have for young, potential researchers?

"Do a lot of research about PhD life before going into it," suggests Simla. "It is very different to Bachelor; in the beginning, that was a shock for me. In a Bachelor's, we have specific tasks and exams. As a researcher, we have to read a lot of papers, choose the papers we read carefully, apply the information in our research, and learn to be independent, which is hard but rewarding. It is also a different style of working - make sure it is right for you!"

Belén has reassuring advice: "It is OK if you don't have everything figured out. Some people told me they were not passionate or good enough. I wasn't top of the class, and there had been times when I had fallen out with physics. But somebody told me 'I think you can do it!'.

"PhD is not only for the best of the best, nor for people who wholeheartedly love their subject. I really love what I'm doing, but there are days when I feel confused, or unsure, or insecure about the path I chose, but that's OK. And people can do it even if they are not a genius.

"A lot of it also luck. I am very happy with what I have achieved so far, but I don't think it's entirely down to merit, things happen. We don't necessarily work harder than people who didn't do a PhD.

"I would also say never be afraid to ask for help. For the first few months I was a bit shy and I felt that nothing was working, but at some point I just told myself 'ask someone'. And I got really helpful insights! People such as post-docs and supervisors, even people at conferences, can really make a difference."

"Also you have to work in teams," adds Simla. "The most successful work in the literature always comes from teams. My professor states that 90% of what he learned was from peers, not supervisors."

"And you have to delegate," says Lara. "At the beginning I was possessive of my code, but I had to learn to delegate when when I started getting overwhelmed!"

"I was using a programming tool and I found ways to add to and improve it," relates Belén, "and somebody asked me 'Why don't you contact the original developer? He might appreciate this," and so I did, and not only he did he appreciate it, but most importantly, he also had very helpful comments!"

"Choosing the right area of research is vital," according to Simla: "My professor often says that if you do what you love, you don't have to work for the rest of your life."

Interview: John Maxwell

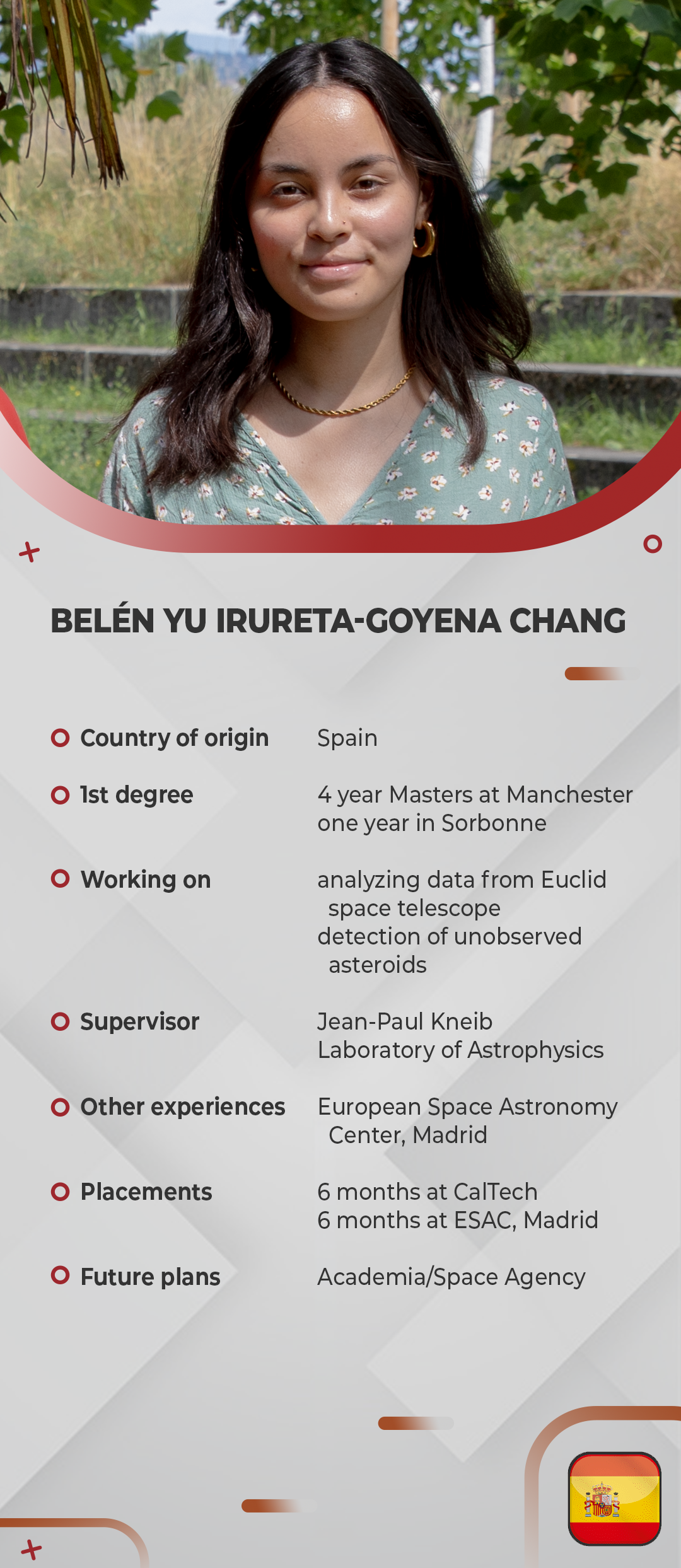

Photos and collectible cards: Alex Widerski